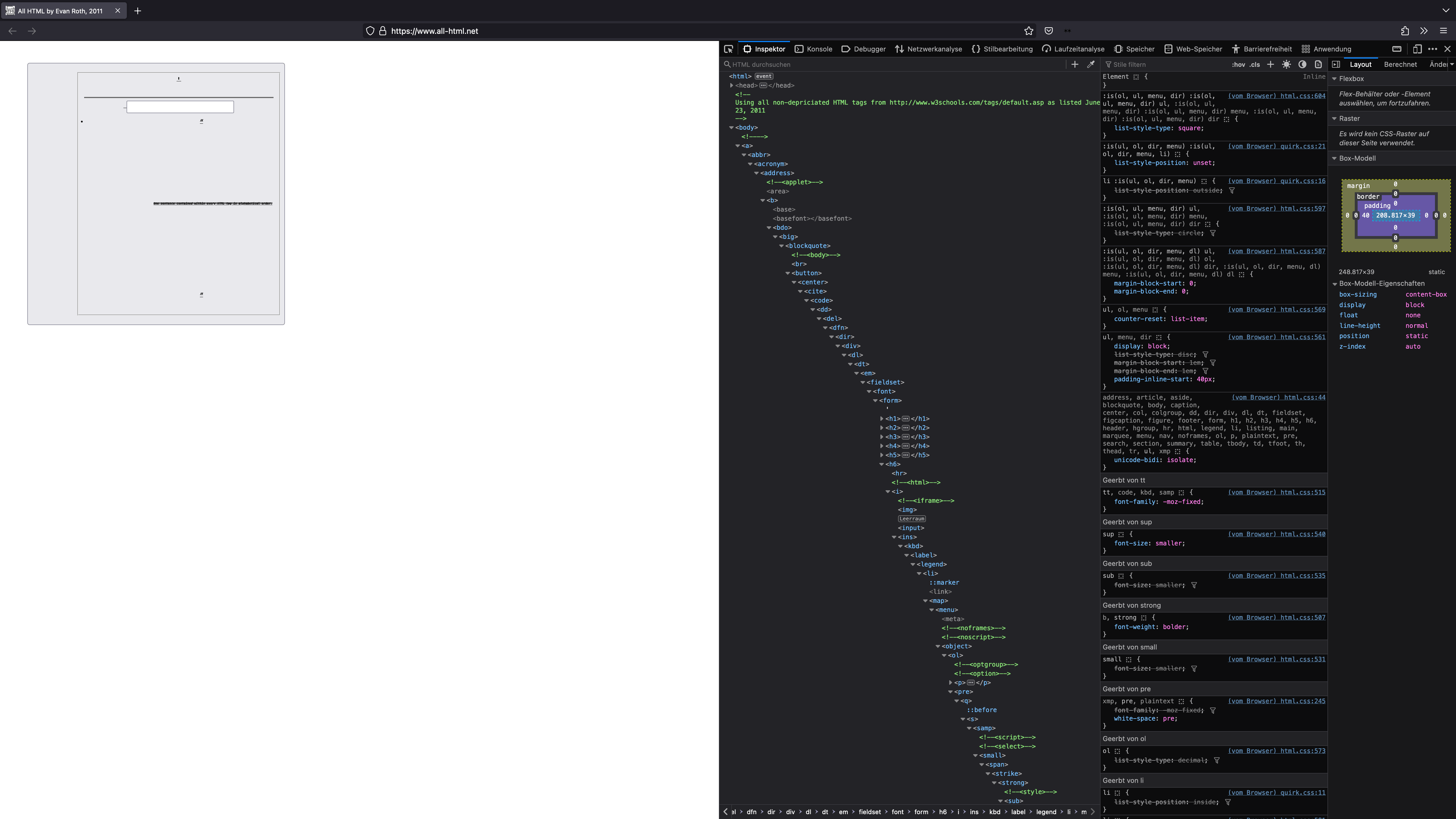

An intro to HTML

HyperText Markup Language

HTML is the standard markup language/format for creating web pages, containing the content and structure of a page as a series of tags/elements.

-

HTML | MDN

When in doubt, refer to the MozillaDeveloperNetwork documentation! -

W3Schools is another very popular resource for code learning online, but MDN is a lot more comprehensive.

-

Basics of HTML

A very calming introduction by Laurel Schwulst. -

Organizing Files for the Web

Sasha Portis on (web) file-naming, for when you get to saving. -

Avoid Geeks for Geeks.

HTML is the skeleton of the web. At its most basic it is a text file, in a folder on a computer, with a .html extension.

This format was codified by our pal Tim Berners-Lee in 1991, evolving from his earlier SGML, a similar proto language. There have been five major revisions to the spec since then, which added (and sometimes deprecated, or removed) tags and syntax:

- HTML 1, 1991

- HTML 2, 1995

- HTML 3, 1997

- HTML 4, 1997 (busy year)

- HTML 5, 2014

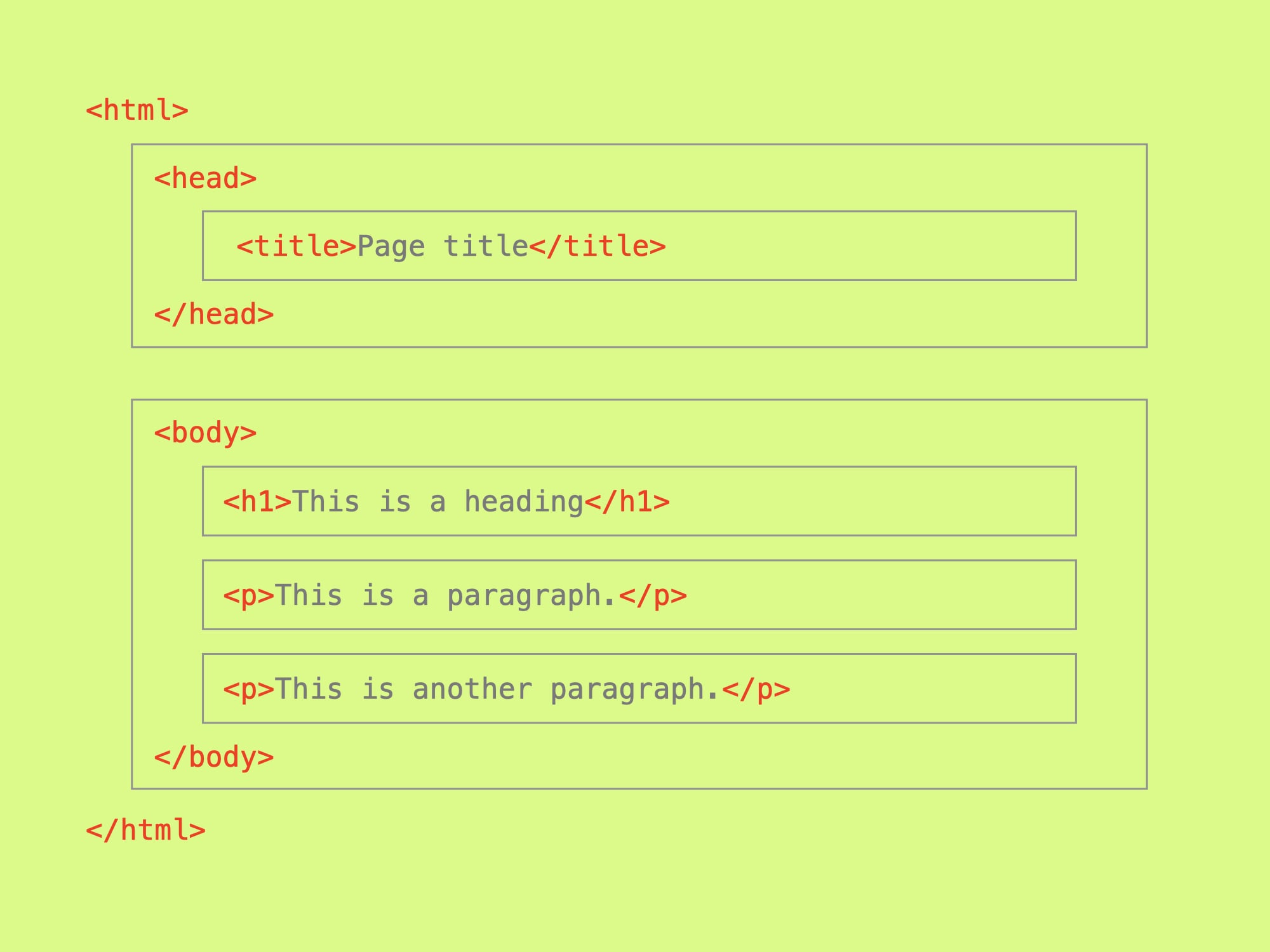

Semantics

HTML consists of a range of elements, nested inside one another.

As a visual:

As code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Page title</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is a heading</h1>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

<p>This is another paragraph.</p>

</body>

</html>The <html> element contains all elements of the page, the <head> element contains the title, and the <body> contains <h1> and <p>.

We call these semantic elements—which is saying that they give their contents a meaning or a role. These roles are then interpreted by your browser (Chrome, Safari, Firefox, etc.) when it loads the file, to ultimately display the page. We call this parsing the document.

The Semantic Web is not a separate Web but an extension of the current one, in which information is given well-defined meaning, better enabling computers and people to work in cooperation.

In our example, here is what we’ve told the computer:

-

<!DOCTYPE html>

What kind of file this is, so it knows how to parse it. -

<html>

The root element of an HTML page, containing all the content. -

<head>

The meta information about the HTML page—like its title, default language, scripts, and stylesheets. -

<title>

Specifies a title for the page—which is shown in the browser’s tab, and when it is shared. -

<body>

Defines the document's body—the container for all the visible contents, such as headings, paragraphs, images, hyperlinks, tables, lists, etc. -

<h1>

Defines a primary/first-level heading. -

<p>

Defines a paragraph.

We use semantic elements to help structure and describe our content—but also for accessibility (screen readers)—where the tag type helps indicate what things are. Don't use divs to structure a website.

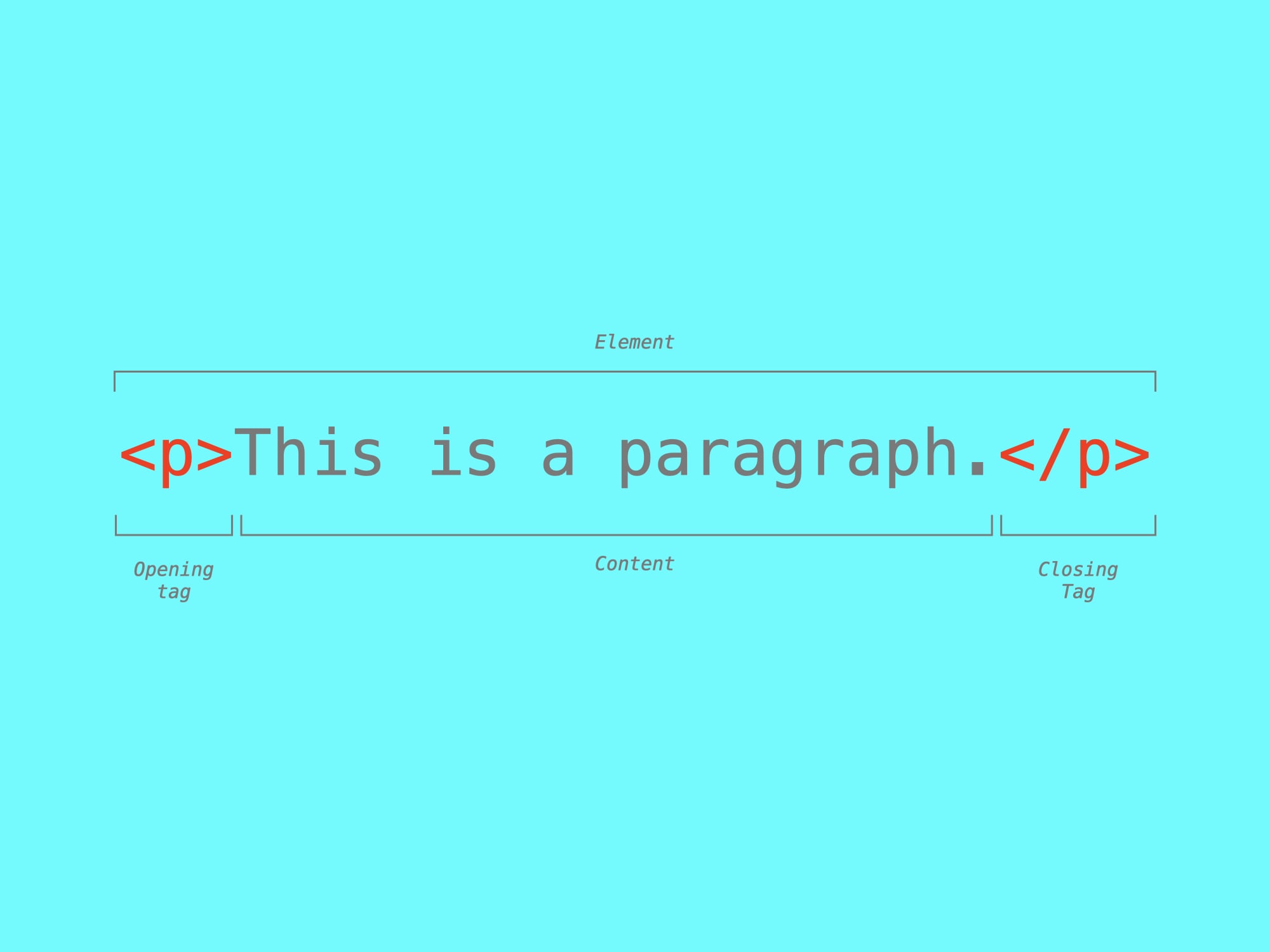

Elements

Elements are composed of tags (opening, closing) and their content:

Some elements do not have any content or children, like <br> or <img>. These are called empty elements and do not have a closing tag.

Common elements

Headings

<h1> <h2> <h3> <h4> <h5> <h6> for headings

<h1>There should only be one first-level heading!</h1>Paragraphs

<p> for paragraphs.

<p>You should always wrap your text in a paragraph!</p>Links

<a> are links.

<a href="https://www.example.com">Links need attributes!</a>The href (hypertext reference) specifies a URL that the link points to. The <a> tag wraps the visible link text. The href can point to another, local HTML file (living in the same directory structure) or an external page. They can also point to specific parts of a page. This is either done by specifying the relative or absolute URL/path within the href attribute.

Understanding how to locate files on your computer or other elements within a document is crucial for making a functioning hyperlink. Make sure to read up on:

- MDN, Dealing with files - MDN, What is a URL? - MDN, Creating hyperlinks

Images

<img> are images.

The src likewise can point to a local image file or an external URL! alt provides a description for accessibility/screen readers.

<img src="example.jpg" alt="Images should have descriptions!">Header, Main, Footer

<header> <footer> <nav> <main> <article> <section> <div> define areas.

These are the structural containers of a website. The names don’t imbue meaning or function directly, but help us organize and think about our content structure. (And again, are helpful for accessibility.)

<body>

<header>

<!-- A header. -->

</header>

<main>

<!-- Your main content. -->

</main>

<footer>

<!-- The footer. -->

</footer>

</body>Formatting

<strong> <em> <cite> <i> <mark> and more wrap around bits of text and are used for various formatting purposes.

<p>You may have noticed I like using <i>italic</i> and <mark>highlights</mark>.</p>Lists

<ol> <ul>, and <li> build lists

<ul>

<li><!-- A list item. --></li>

<li><!-- Another. --></li>

<li><!-- A third. --></li>

</ul>There are many, many HTML elements, all with particular uses. (We’ll unpack some more, below.)

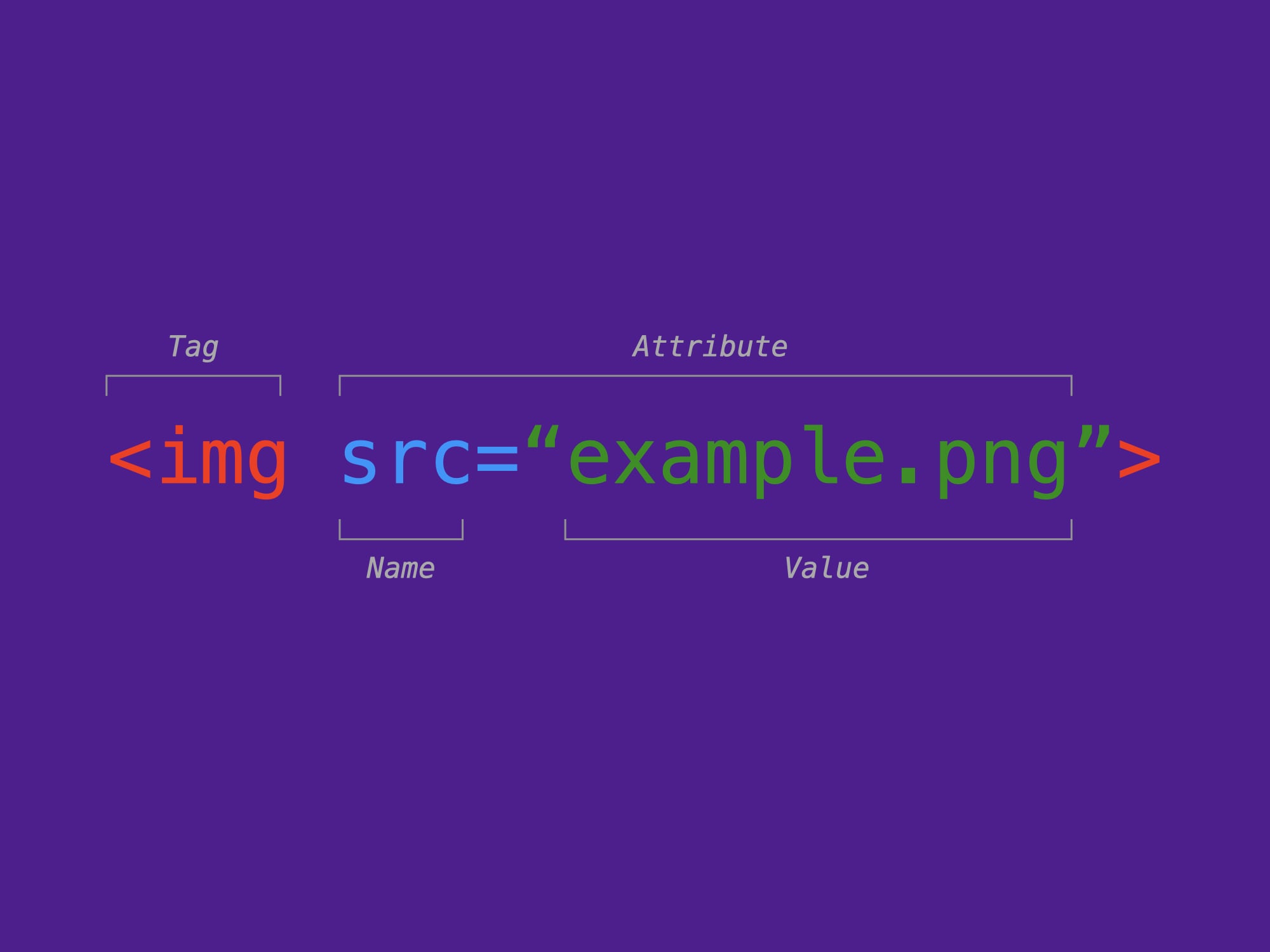

Attributes

All HTML elements can have attributes, which provide more information about the element:

Common attributes

-

The

langattribute of the<html>tag declares the language of the Web page.<html lang="en"> -

The

hrefattribute of<a>specifies the URL of the page the link goes to.<a href="https://www.example.com">Goes to example.com</a> -

The

targetattribute_blankcan tell a<a>to open in a new window/tab.<a href="https://www.example.com" target="_blank">New tab!</a>This can be annoying, so use it judiciously!

-

The

styleattribute is used to add styles to an element, such as color, font, size, etc.<p style="color: blue;">This is blue text.</p>We’ll use CSS for this kind of thing, but know this is how it used to be done and it was brittle and terrible.

-

The

srcattribute of<img>specifies the path to the image to be displayed, as above.<img src="example.jpg"> -

The

widthandheightattributes of<img>provide size information for images. Not required, but helps prevent layout “sloshing” as images load.<img src="example.jpg" width="200px" height="200px"> -

The

altattribute of<img>provides an alternate text for an image, used by screen readers.<img src="example.jpg" alt="A description of the image."> -

The

idspecifies a singular, unique element on a page—for CSS targeting and anchor (scroll, “jump”) links, prepended with#.<h2 id="a-heading-element">A heading element</h2> <a href="#a-heading-element">Goes to “a heading element”</a> -

The

classattribute provides a selector took hook on with CSS.<p class="warning">We’ll get into this soon.</p>

Parsing and readability

Capitalization, extra white space, or line breaks are unimportant for html. (It does matter for servers and in URLs though.) The browser will just read everything inside an html file from left to right, as if it is one long, running sentence. So the shouty <HTML> and quieter <html> are interpreted the same.

The browser parses both of these in the exact same way:

<body>

<h1>Dog Breeds</h1>

<p>There are many kind of dog breeds</p>

<ul>

<li>German Shepherd</li>

<li>Bulldog</li>

<li>Poodle</li>

</ul>

</body><body><h1>Dog Breeds</h1><p>There are many kind of dog breeds</p><ul><li>German Shepherd</li><li>Bulldog</li><li>Poodle</li></ul></body>But obviously, indented code is much more readable to us humans. We can use whitespace, tabs/indenting, and line breaks to make it easier for us to read the code. There are a lot of common patterns used—like indenting to indicate hierarchy/nesting. But there are also no wrong ways to do it!

Code is read more often than it is written. Code should always be written in a way that promotes readability.

Block elements

Block-level elements always start on a new line, and take up the full width available—stretching out to the left and right of their parent/container. They stack on top of each other:

<address>

<article>

<aside>

<blockquote>

<canvas>

<dd>

<div>

<dl>

<dt> <fieldset>

<figcaption>

<figure>

<footer>

<form>

<h1>–<h6>

<header>

<hr> <li>

<main>

<nav>

<noscript>

<ol>

<p>

<pre>

<section>

<table>

<tfoot> <ul>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Block elements</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Blocks are full-width</h1>

<p>Longer text will wrap internally within each block element.</p>

<p>Other blocks will then stack underneath.</p>

<aside>

<p>They can still be nested.</p>

<p>And will push down the page.</p>

</aside>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Block elements</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Blocks are full-width</h1>

<p>Longer text will wrap internally within each block element.</p>

<p>Other blocks will then stack underneath.</p>

<aside>

<p>They can still be nested.</p>

<p>And will push down the page.</p>

</aside>

</body>

</html>Inline elements

Inline elements do not start on a new line, and only take up as much width as necessary. Other text and inline elements will continue to flow around them, and they can wrap to new lines:

<em>

<strong>

<span>

<a>

<img>

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Inline elements</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Inline elements flow <em>within</em> a block</h1>

<p>To give it different <strong>meaning</strong>.</p>

<p>Or <span style="color: red;">style</span> it.</p>

<p>Or <a href="/topic/html">link it</a> somewhere.</p>

<p>Images default <img src="tim.jpg"> to inline.</p>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Inline elements</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Inline elements flow <em>within</em> a block</h1>

<p>To give it different <strong>meaning</strong>.</p>

<p>Or <span style="color: red;">style</span> it.</p>

<p>Or <a href="/topic/html">link it</a> somewhere.</p>

<p>Images default <img src="../../images/lecture-02/tim.jpg"> to inline.</p>

</body>

</html>So many elements!

Comments

You can comment part of the code and the browser won’t show it. Comments are often used to explain your thinking, organize your code, “turn off” a bit of code, or hide whatever you’d like.

In VS Code on Mac you can toggle comments by pressing cmd + / .

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Comments</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Sometimes you want to note something while coding.</p>

<!-- This text will not be shown in the browser! -->

<p>You can write these notes in comments.</p>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Comments</title>

</head>

<body>

<p>Sometimes you want to note something while coding.</p>

<!-- This text will not be shown in the browser! -->

<p>You can write these notes in comments.</p>

</body>

</html>Keep in mind these are still readable in the source.

I highly recommend getting into a habit of commenting your code, especially when starting out. If you figure something tricky out, write down why and how you solved it to help you understand and remember. And you’ll often come back to things. Commenting your code is a gift to your future self!

Tables

Tables aren’t used as often anymore, in favor of <div> and other layout elements. You used to have to use them to get any kind of multi-column, grid layouts. But those need even more CSS!

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Tables</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A basic table</h1>

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Header</th>

<th>Another header</th>

<th>Still a header</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>A cell</td>

<td>Another cell</td>

<td>Still a cell</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Tables</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A basic table</h1>

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>Header</th>

<th>Another header</th>

<th>Still a header</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>A cell</td>

<td>Another cell</td>

<td>Still a cell</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>

</body>

</html>This syntax is pretty verbose, for what you get.

Lists

Any time you have more than two of something, you probably have a list. These are commonly used for semantic navigation elements, as well, think “here’s a list of links in this site.”

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Lists</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Lists help you organize</h1>

<h2>There are <em>ordered</em> lists</h2>

<ol>

<li>First item</li>

<li>Second item</li>

<li>Third item</li>

</ol>

<h2>And <em>unordered</em> ones</h2>

<ul>

<li>An item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

</ul>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Lists</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Lists help you organize</h1>

<h2>There are <em>ordered</em> lists</h2>

<ol>

<li>First item</li>

<li>Second item</li>

<li>Third item</li>

</ol>

<h2>And <em>unordered</em> ones</h2>

<ul>

<li>An item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

<li>Another item</li>

</ul>

</body>

</html>Description lists

There are specific lists for defining things.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Description lists</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Description lists are underused!</h1>

<dl>

<dt>This is a term</dt>

<dd>And then a definition</dd>

<dd>You can have multiple definitions</dd>

<dt>Another term</dt>

<dd>Another definition</dd>

</dl>

</html>These aren’t much to look at without CSS, though. Soon!

Details/summary

There is even some basic interactivity (way, way ahead of JavaScript) with details disclosure elements that open and close.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Details/summary</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Details/summary are interactive</h1>

<details>

<summary>Clicking this toggles the element</summary>

<p>You can have any content down here.<p>

<p>Multiple elements, whatever you want.<p>

</details>

<details open>

<summary>They also can be open to start</summary>

<p>This will already be visible.<p>

</details>

</body>

</html><!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Details/summary</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Details/summary are interactive</h1>

<details>

<summary>Clicking this toggles the element</summary>

<p>You can have any content down here.<p>

<p>Multiple elements, whatever you want.<p>

</details>

<details open>

<summary>They also can be open to start</summary>

<p>This will already be visible.<p>

</details>

</body>

</html>You can do a lot with these.

Again, there are many, many, many, many HTML elements. Try and find the one that best fits your usage, wherever possible using a semantic element that fits your content.

User-agent styles

We haven’t applied any styles/CSS here yet, so everything we see in these examples is based on user-agent stylesheets—that is, each browser’s own default display (and behavior) for an element type. This is what the web was, before CSS! But not always what you want. We’ll get into writing our own styles in the coming weeks.

3.2. Priority of Constituencies

In case of conflict, consider users over authors over implementors over specifiers over theoretical purity. In other words costs or difficulties to the user should be given more weight than costs to authors; which in turn should be given more weight than costs to implementors; which should be given more weight than costs to authors of the spec itself, which should be given more weight than those proposing changes for theoretical reasons alone. Of course, it is preferred to make things better for multiple constituencies at once.

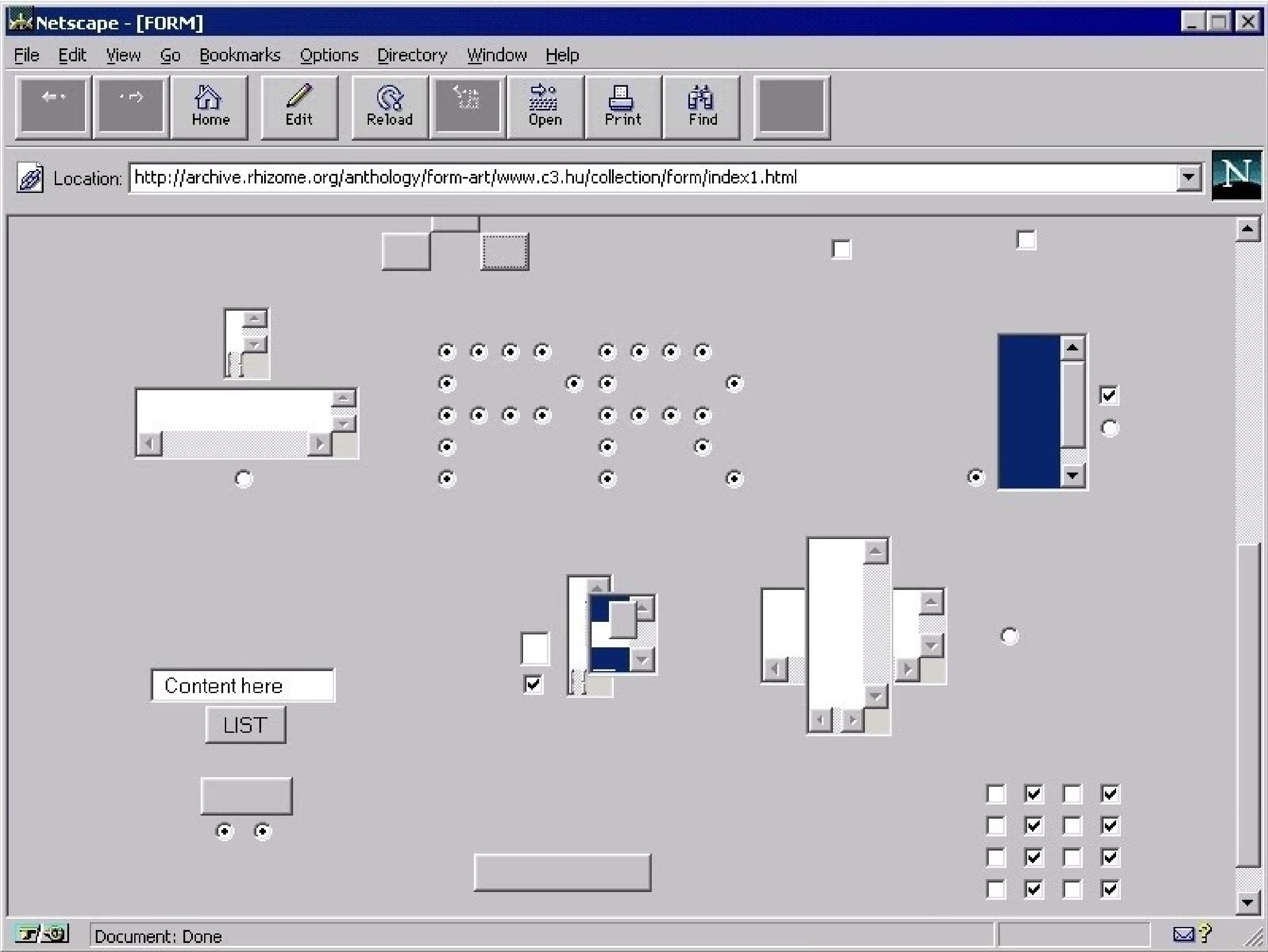

Limitations

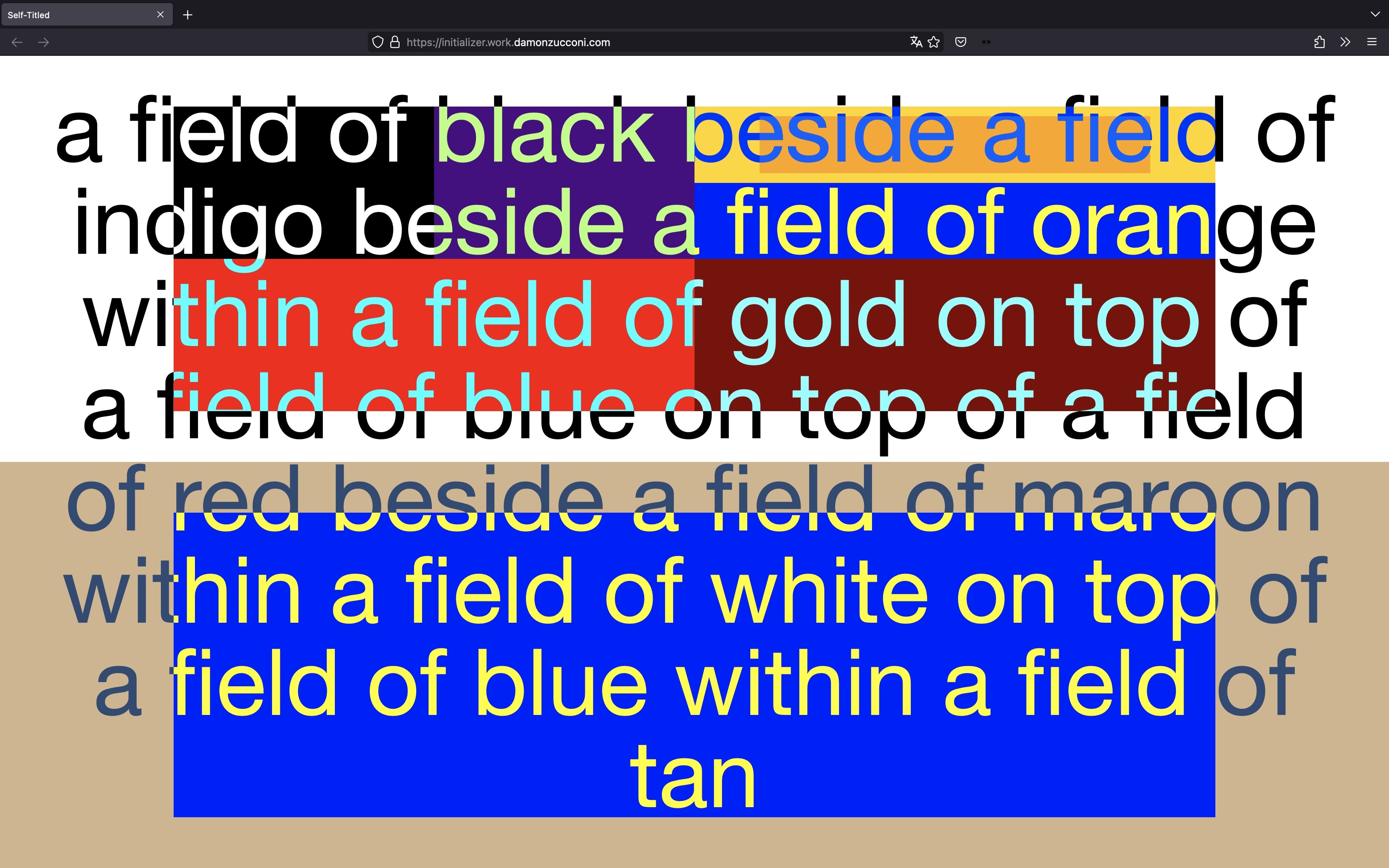

So far we are limited to writing plain HTML. But sometimes words on a page, or just structure on a page is all you need to make something. A lot books and concrete poetry happened like this. Also online you can find a lot of websites that only use structural HTML elements.

- Alexei Shulgin turns online bureaucracy into Form Art.

- Self-Titled, Damon Zucconi'swork explains itself

This page was adapted (ever so slightly) from Michael Fehrenbach's HTML Intro.