Media Queries

What is responsive design?

Let’s first take a minute to talk about responsive design. This term was coined in 2010 or so by Ethan Marcotte—wrapping a name around a progressive enhancement and mobile first web design approach/

- Responsive design | MDN

- Beginner's guide to media queries | MDN

- Using media queries | MDN

- Using CSS custom properties | MDN

There was a confluence of events that allowed this: modern,

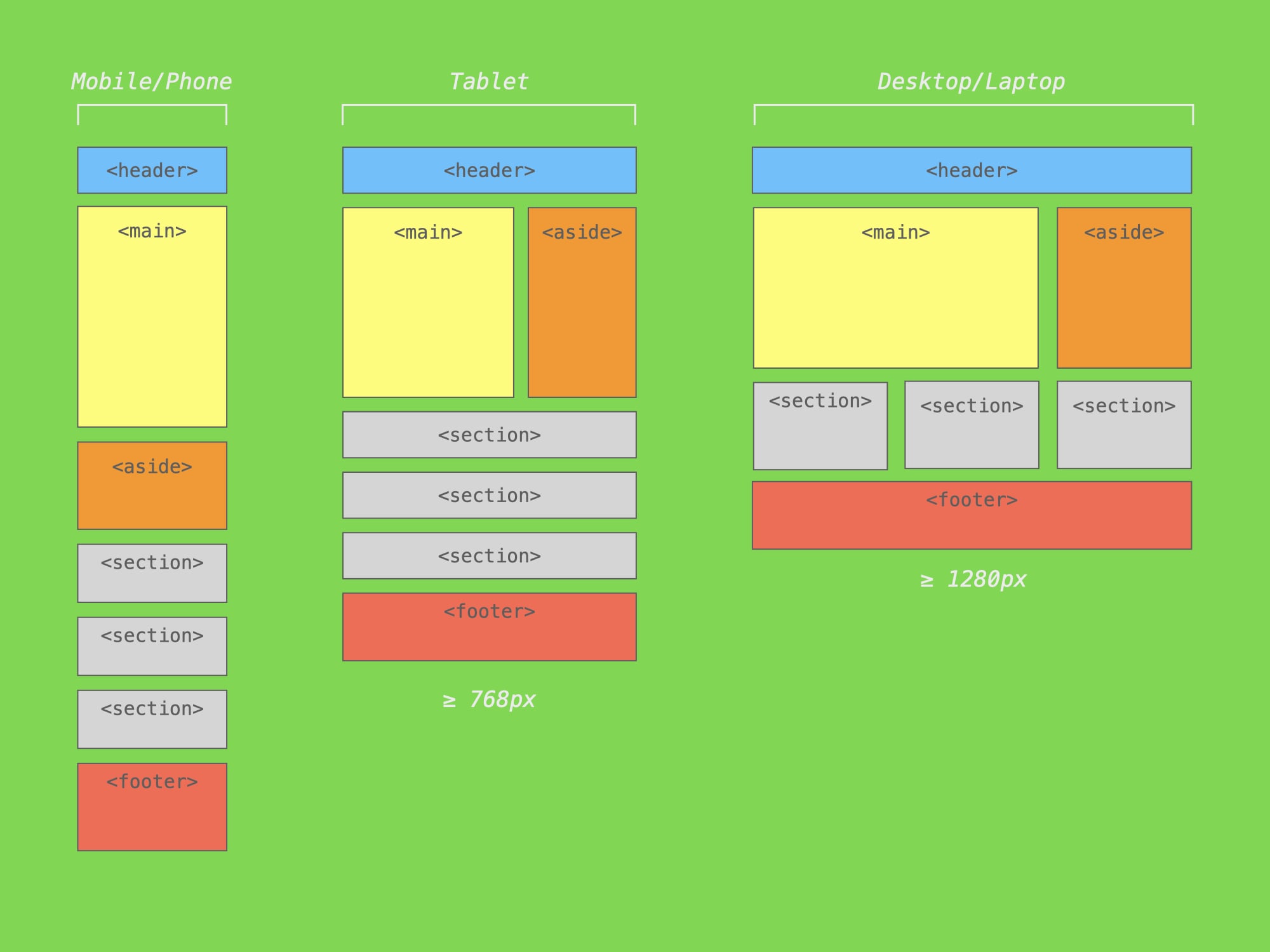

A typical/example responsive layout, adjusting the layout to reflow based on the device width.

The viewport

You’ll see this in the <head> of most websites, these days:

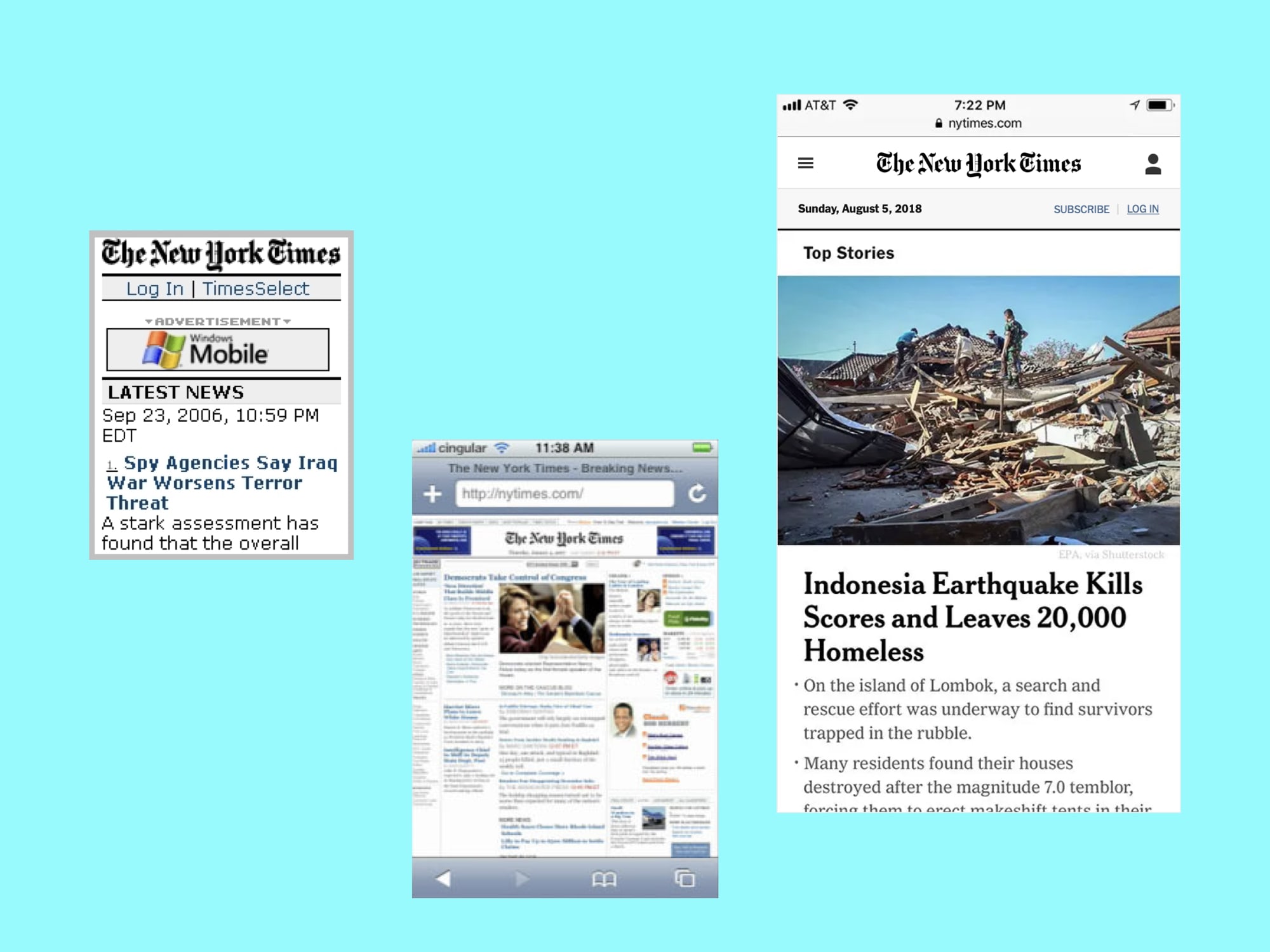

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">When the iPhone came on the scene, most websites didn’t have narrow/smaller (responsive) layouts so the phone would instead scale or zoom out a desktop site design to fit.

Prior to the iPhone, some sites had barebones WAP mobile versions.

In the middle: The full desktop site, scaled down, in 2007. Simpler times.

The Times wasn’t fully responsive until 2018, if you can believe it. (They had a separate mobile site and apps.)

Websites at the time were often designed to a standard width (usually 960px), which the phone shrank down to its 320px screen—and then the user could zoom in or out. It worked—and all the content was there, unlike most mobile sites—but it was less than ideal.

This meta element tells the browser not to do this. It says, “I have a responsive design! Render me at my actual size.”

The width=device-width tells the browser to use whatever the screen’s actual pixel dimension is, and initial-scale=1 sets the starting zoom for the page to 100%. This is how the browser knows how to make the page respond, and how our CSS rules know what width to use.

We call the portion of the page visible at one time the viewport.

Media queries

Responsive design could only really flourish when CSS added the @media at-rule around the same time.

These are colloquially called media queries, and they allow us to check if screen is a certain width or resolution (or other features, which we’ll get to)—and then apply selective CSS only in that scenario. These let site layouts respond intentionally to different devices, for the first time.

Practically, these are blocks of CSS—a little bit like selectors that contain other selectors—but which only apply conditionally when the test/criteria is met.

/* Our CSS has all been out here! */

@media some-criteria-or-rule {

/* CSS that only applies if the test passes. */

}These blocks are like any other CSS—if there are multiple conditions that are met, or there is a tie between properties—the rules cascade down and the lowest/last one takes precedent.

Width-based breakpoints

There are lots of media queries we can use, but we’ll start with width—which is by far the most commonly used and really the core of responsive design. Usually when people are talking about a page or site being responsive, they mean with regards to width.

Width will vary the most between devices—from the 375px–428px of your phones, through the ~ 1440px–1680px of your laptops, up to the ~ 2560px–3440px you might see on desktop displays. Since this width is usually our primary design constraint (height being handled with scrolling), we need width-based media queries to adjust our layouts across this wide range, lest our designs implode.

This is done in steps, at different widths, that we call breakpoints—the window/device/viewport sizes where the content starts to break, if it is not adjusted. This might be because lines of text get too short or too long, becoming hard to read. It might be to prevent a grid of images from becoming too small on a phone—while you can have many columns on desktop, often you can only have one or two on mobile. You can add as many breakpoints as you need to make your page/design work across devices. Don’t write for specific devices; write for your design and your content!

There are very, very few layouts that won’t need some amount of horizontal responsiveness/breakpoints!

In this example, we would refer to 400px as our breakpoint:

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (min-width: 400px) {

div { background-color: lightblue; }

}<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>Drag the code/example divider to see it respond to the media query!

This width rule/test/criteria uses the same syntax as length properties, meaning you can use min-width, width, and max-width.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (min-width: 400px) {

div:first-of-type { background-color: lightblue; }

}

@media (width: 400px) {

div:nth-child(2) { background-color: orange; }

}

@media (max-width: 400px) {

div:last-of-type { background-color: yellowgreen; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }

<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>And a third one, to have an element for each rule. I probably should just grab some lorem ipsum, but at this point I’m committed to typing nonsense.</p>

</div>Again, drag the divider to see rules apply. Exact matches (like the width: 400px; here) are rarely useful!

Height-based, too

You can also use height in the same way—though again, with the normal, vertical scrolling paradigm, height-based adjustments aren’t as necessary or nearly as common.

This example is the same breakpoint of 400px, but now using height:

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (min-height: 400px) {

div:first-of-type { background-color: lightblue; }

}

@media (height: 400px) {

div:nth-child(2) { background-color: orange; }

}

@media (max-height: 400px) {

div:last-of-type { background-color: yellowgreen; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>And a third one, to have an element for each rule. I probably should just grab some lorem ipsum, but at this point I’m committed to typing nonsense.</p>

</div>These code examples are responsive, themselves—stacking like this when they are narrow.

In a broader code/programming context, it can be helpful to think of media queries as conditional if statements. “If this thing is true, then do this.” (You may have heard of If This Then That.) We’ll talk about this later with JavaScript, where conditionals are ubiquitous and powerful.

Orientation

You can also be less specific about your width/height and instead use orientation—like when you rotate your phone. The queries use the wonderfully tenacious names/values of portrait or landscape.

(Everything was a painting before it was a photograph or a web page.)

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (orientation: portrait) {

div:first-of-type { background-color: orange; }

}

@media (orientation: landscape) {

div:last-of-type { background-color: yellowgreen; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; } <div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>Drag the divider to make the example narrower.

And/or combinations

And speaking of *conditional statements—*you can also merge multiple media queries into one test/check, using and. This is often used for a range (to apply something between two breakpoints) or to combine width and height checks, together.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (min-width: 400px) and (max-width: 600px) {

div:first-of-type { background-color: orange; }

}

@media (min-width: 300px) and (min-height: 300px) {

div:last-of-type { background-color: yellowgreen; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>The demo here is taller than 300px, for the second one.

You can also use comma-separated queries (like selector lists) to apply or logic—setting the same styles for different scenarios.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media

(max-width: 300px),

(min-width: 500px) {

div { background-color: yellowgreen; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

div:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>Note that you could do this with and, as in the example above, by just swapping the colors. Code logic!

There is also a not logic operator—which will reverse the meaning of the media query. But this syntax tends to be really, really confusing—especially with things like min / max rules making for double-negatives. So it is easier to avoid!

Why say not portrait when you can just say… landscape?

Mobile-first design

So this can all get very complicated, very quickly—especially with complex designs, overlapping rules, and the wide ranges of devices to consider. One of the easiest methodologies to keep things understandable is practicing mobile first design/development. This has become kind of buzzwordy in the past decade or so, but it is a good philosophy to adhere to nonetheless.

Your design constraints will be tighter, by tackling your smallest layout first—but it is almost always easier to scale things up than down. A mobile design can always work as a passable desktop one; the reverse is rarely true.

(Another way to think of it: if it doesn’t work on mobile, it doesn’t work.)

-

In your design, mobile first means considering small screens and then adding complexity, limits, or considerations for larger/desktop screens.

-

In your HTML/CSS development, this means writing your styles for mobile… first, then adding

min-widthbreakpoints (below them) to progressively enhance your design as it scales up.

section {

display: flex; /* We’ll talk about flex soon! */

flex-wrap: wrap;

gap: 10px;

}

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (min-width: 400px) {

div {

background-color: yellowgreen;

width: calc((100% - 10px) / 2);

}

}

@media (min-width: 500px) {

div {

background-color: orange;

width: calc((100% - 30px) / 4);

}

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

p:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }

<section>

<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>And a third one, to have an element for each rule. I probably should just grab some lorem ipsum, but at this point I’m committed to typing nonsense.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>Let’s have a fourth one here, to better help show a multi-column layout as we get wider. Writing dummy text manually is oddly calming?</p>

</div>

</section>The width here are kind of tricky—but this will be much easier with grid, I promise!

This follows the general CSS paradigm of the cascade—and is much, much, much easier than adjusting desktop front-end after the fact. Always think mobile first!

Briefly, CSS variables

Custom properties (I’ll almost always say CSS variables) aren’t strictly a part of responsive design or media queries—but they come up very often in modern, mobile-first practice and we’ll introduce them briefly, here.

These bring the programming concept of variables into CSS. These are shorthand entities for values we want to reuse throughout a document—or, in a responsive context, want to modify at certain breakpoints. (You could think of a color swatch, if you are in an Adobe mindset.) Changing the value of a variable changes it everywhere it is referenced, no copy/pasting or find/replacing. Again, these are for you—it is all the same to the computer. More ergonomics!

In your CSS, you declare (set) these with a -- prefix in front of a subjective name you make up. And you reference (use) them by wrapping that variable name in var():

:root {

/* Declare variable. */

--brand-color: #e42a1d;

}.brand-color {

/* Reference it. */

color: var(--brand-color);

}You can use these as values for any CSS property—colors, spacing, etc.—anything you use multiple times and want to be consistent, or want to easily change.

/* Special selector that means “default”. */

:root {

--font-size: 16px;

--spacing: 20px;

}

@media (min-width: 400px) {

:root {

--font-size: 24px; /* Bump these up. */

--spacing: 40px;

}

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

font-size: var(--font-size); /* Use the size. */

padding: var(--spacing); /* Use the spacing. */

}

div {

/* The second value here is a “fallback”. */

/* It’s used if a variable hasn’t been declared. */

background-color: var(--background, aquamarine);

padding: calc(var(--spacing) / 2); /* Calcs, too. */

}

div:not(:first-of-type) {

--background: yellowgreen; /* Only for this element. */

margin-top: var(--spacing);

}<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

</div>

<div>

<p>This is another responsive element, with some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>Changing the spacing here would be easy, even though we use it a bunch.

You’ll often declare a set of variables for mobile—type sizes, spacing, and so on—and then adjust them, once, for desktop. No need to write all the properties out again, with all their own redundant media-queries! Variables are great.

They’ll help you avoid unwanted cascade (applying the same property), especially across breakpoints. But also help to facilitate design system thinking—focusing your design on the relative relationships of things.

Other media features

The most common media queries, by far, will be width/@media has some more tricks up its sleeve with testing for other browser features. We’ll look at some of the handy/common ones.

screen vs. print

In all of our above examples, there is an implied media type of screen—since that is usually what we are concerned with on the web. But there is also one for print! You can use these to segment styles to one medium or the other.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media screen and (min-width: 400px) {

div {

background-color: lightblue;

}

}

@media print {

div {

background-color: white;

border: 2px solid black;

font-family: serif;

font-size: 18pt;

padding: 0.5in;

}

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

p:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

<p>Some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>You can see the print style in action by the arrow in the upper corner, then ⌘-P to print. It is still A Thing, though often forgotten about in modern web design/projects.

hover

Another common one is hover, to detect whether a browser has an input device that supports hovering—which really just means a mouse, on laptop/desktop computers. Mobile touch-based systems don’t have this behavior (and sometimes react oddly to :hover CSS), so you should adjust your interfaces to work in the absence of this state.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

aside { background: yellowgreen; }

@media (hover: hover) {

aside { visibility: hidden; }

div:hover + aside { visibility: visible; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

aside,

div {

padding: 10px;

}

aside,

div:not(:first-of-type),

p:not(:first-of-type) {

margin-top: 10px;

}<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

<p>Some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

</div>

<aside>This is some really important text that you want to make sure mobile users can see, too!</aside>If you view this on your phone, the aside should be visible without interaction. On your computer, you’ll have to mouse over the div. Note how this is written with a mobile first style, only adding the hover state later/lower for people who have it!

Hover states are a good thing for progressive enhancement, as we did here—to add them in after you have a working mobile design! Since maybe a third to a half of your audience (depending on your project) won’t see them.

prefers-color-scheme

You see this one more and more these days—switching up a site’s styles based on whether the user is in light or dark mode, popularized by the ol’ iPhone again.

div { background-color: aquamarine; }

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

body {

background: black;

color: white;

}

div { background-color: teal; }

}

body {

font-family: cursive;

padding: 20px;

}

div { padding: 10px; }

p:not(:first-of-type) { margin-top: 10px; }<div>

<p>This element is responsive. I’ll add some text here so we have something to look at and so that it wraps, but the text itself isn’t important, at the moment.</p>

<p>Some more text in it. Again the text doesn’t really matter, I just want a bit of stuff in here. A few lines, is all.</p>

<p>If you’re still reading this, I appreciate it.</p>

</div>You’ll see this differently depending on whether your system is in light or dark mode. (Vive le dark mode!)

Sometimes this feels appropriate (especially in products/

Reduced Motion

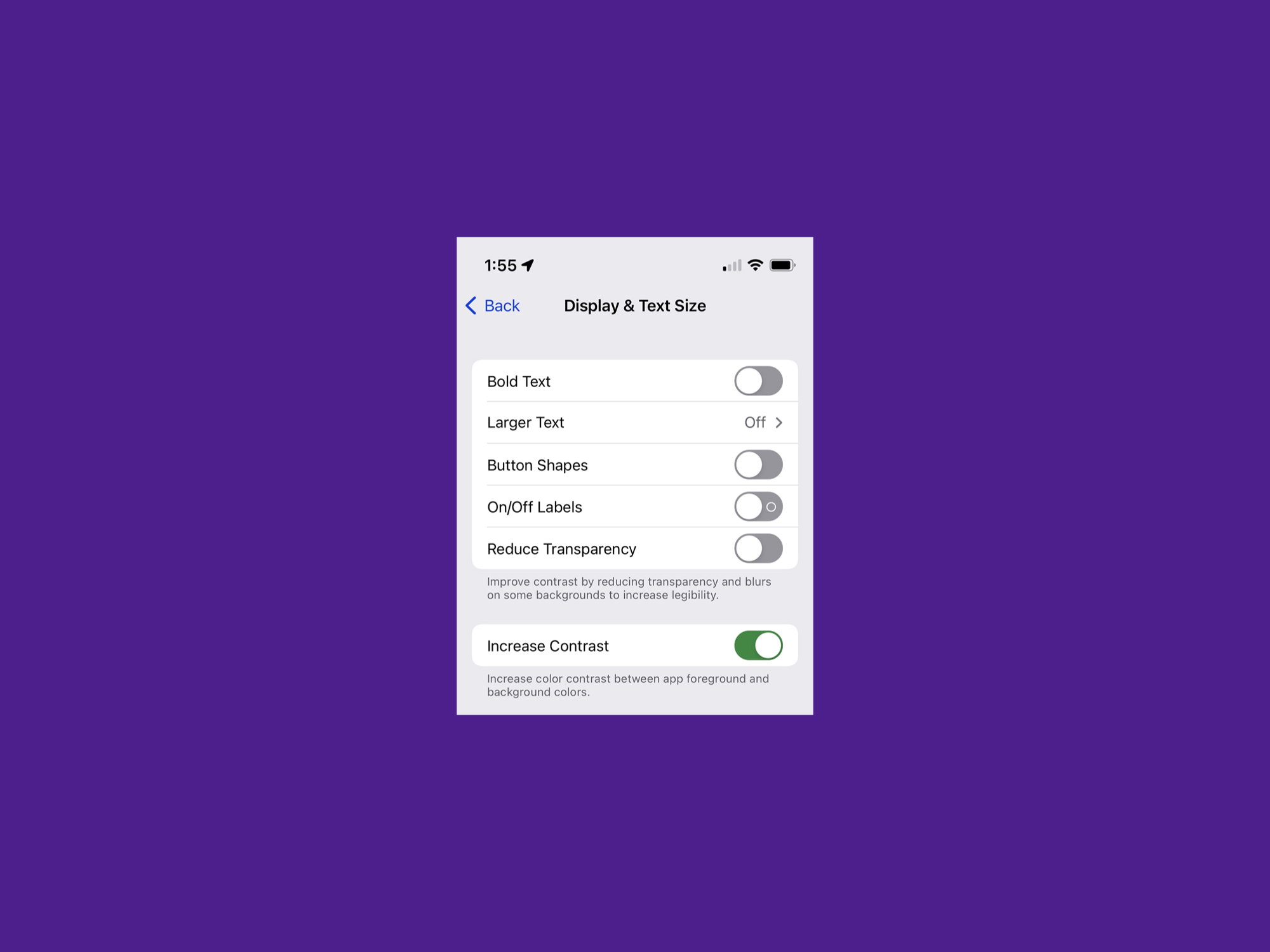

prefers-reduced-motion, prefers-contrast

These last two are primarily concerned with accessiblity, for people who run their device/browser with animations turned off, or in a high-contrast mode to help with their vision.

button {

animation: some-slick-animation;

}

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) {

button { animation: none; }

}

p {

background-color: lightgray;

color: slategray;

}

@media (prefers-contrast: more) {

p {

background-color: white;

color: black;

}

}

The power of the Web is in its universality. Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.

This page was adapted (ever so slightly) from Michael Fehrenbach's page on media queries.